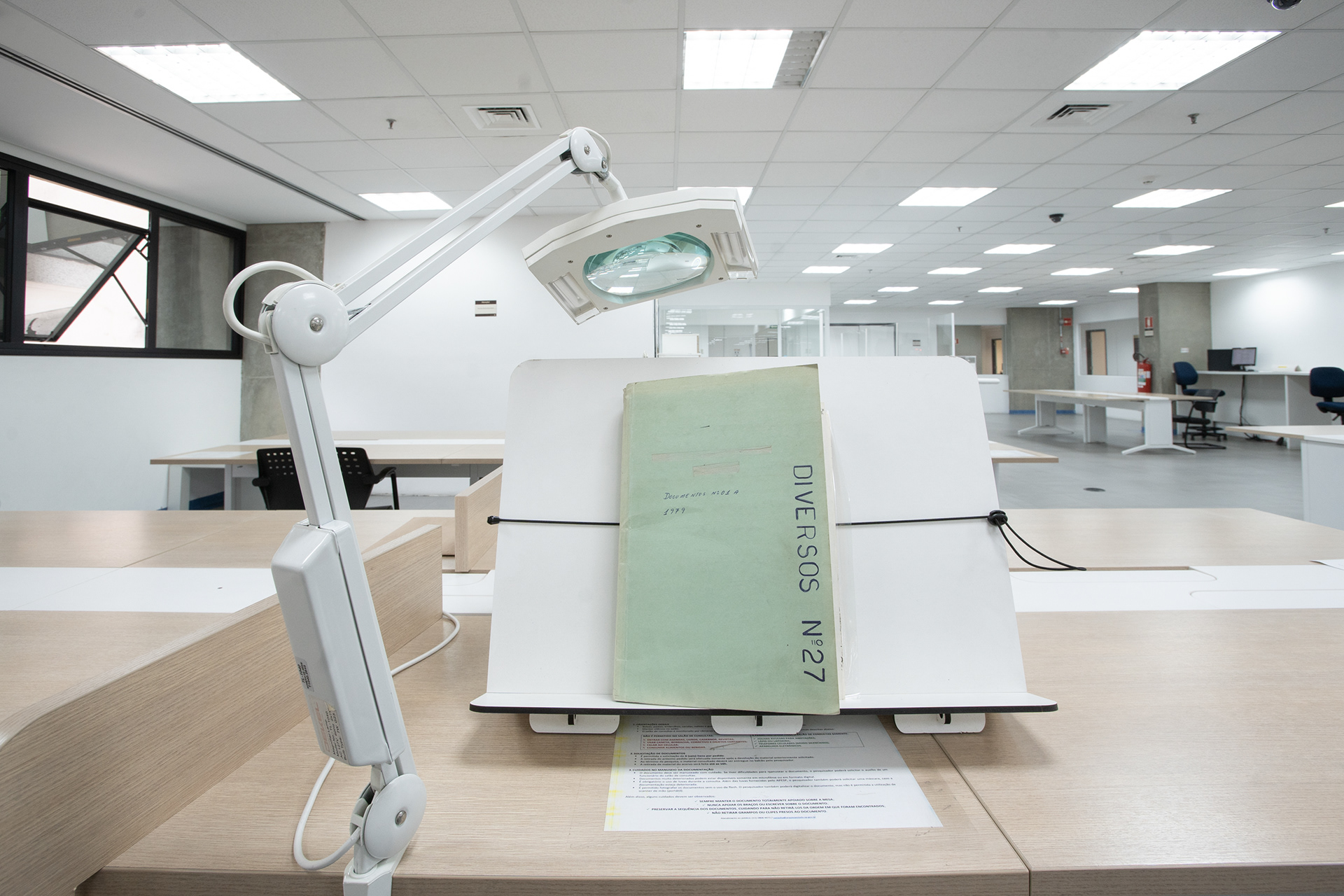

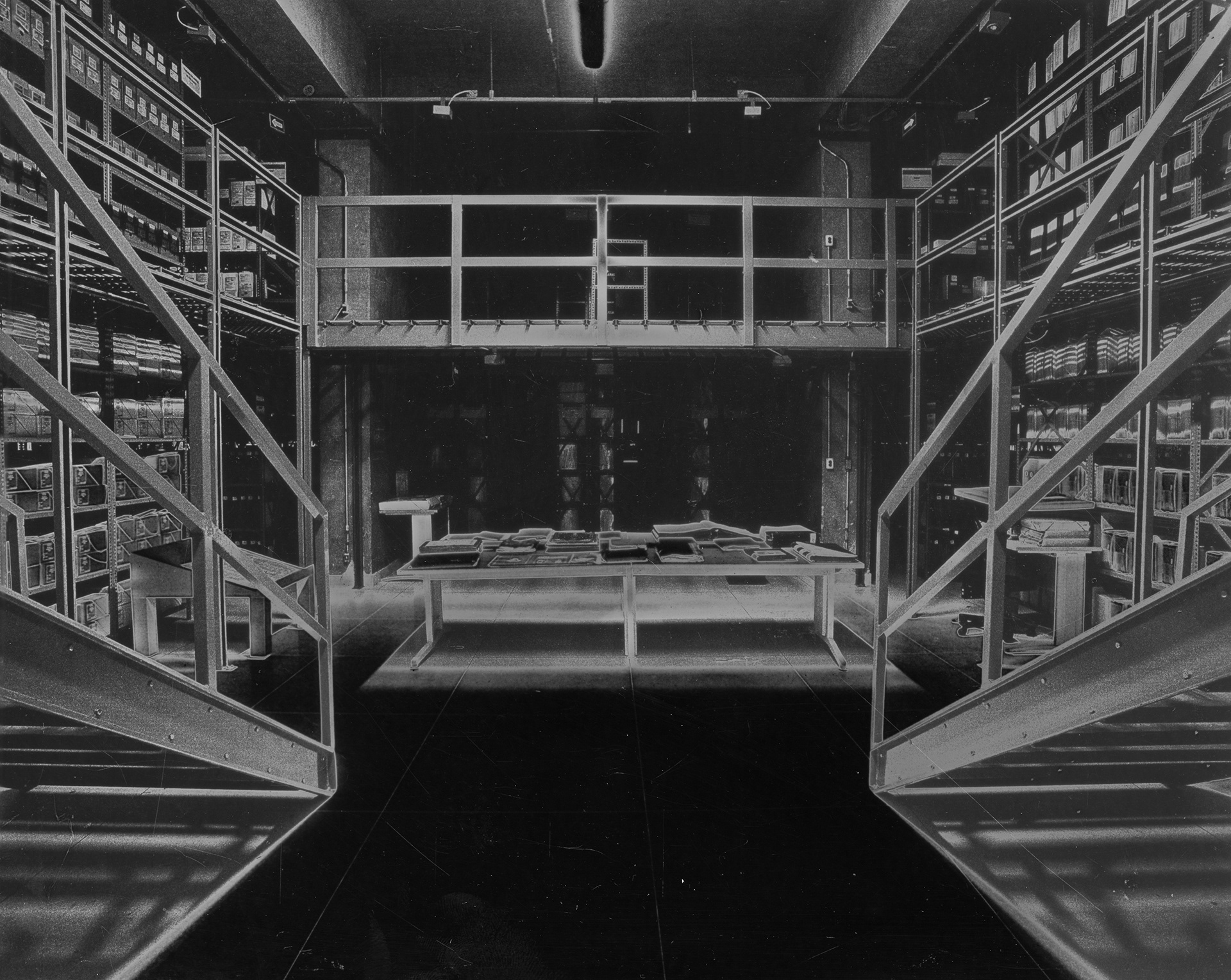

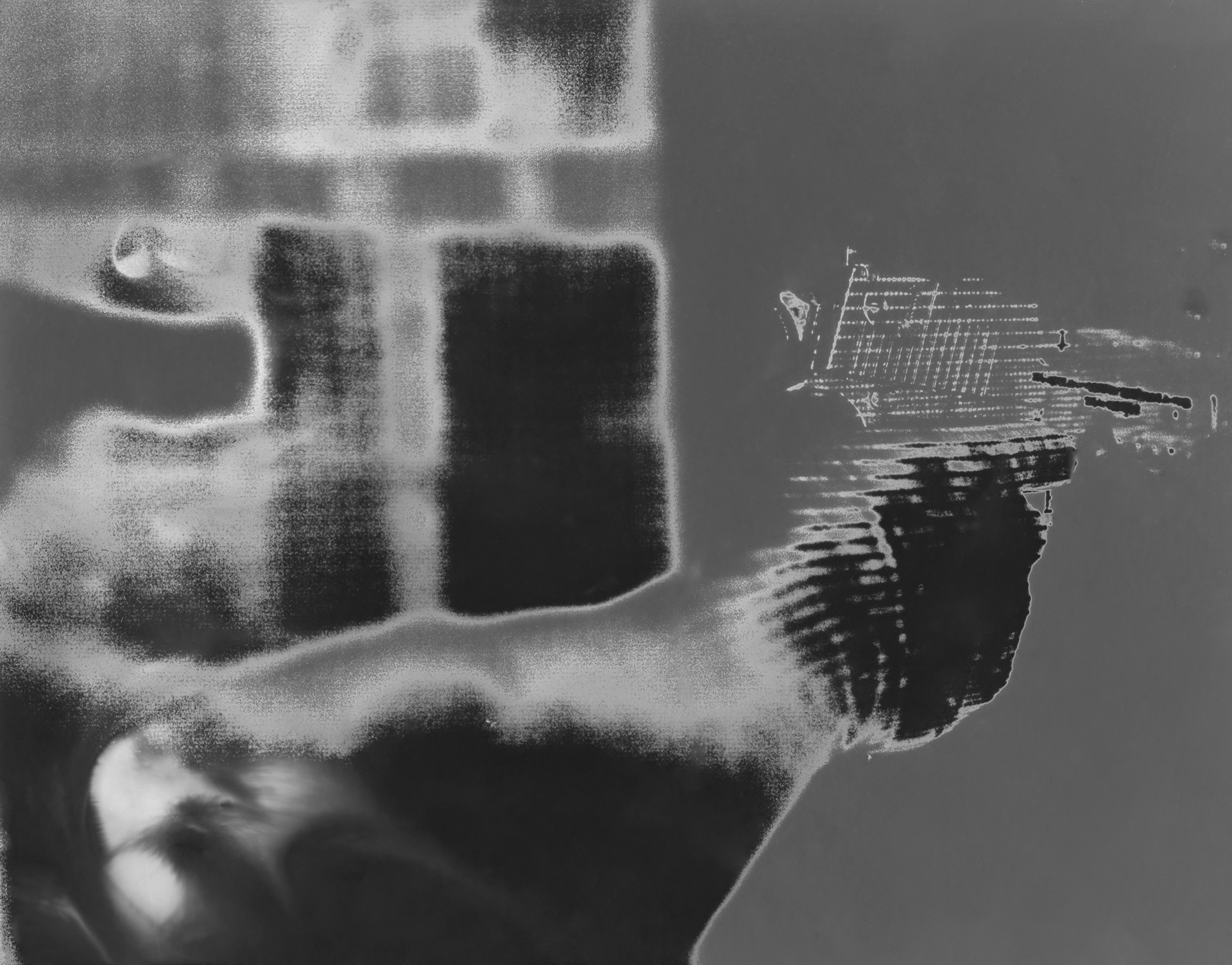

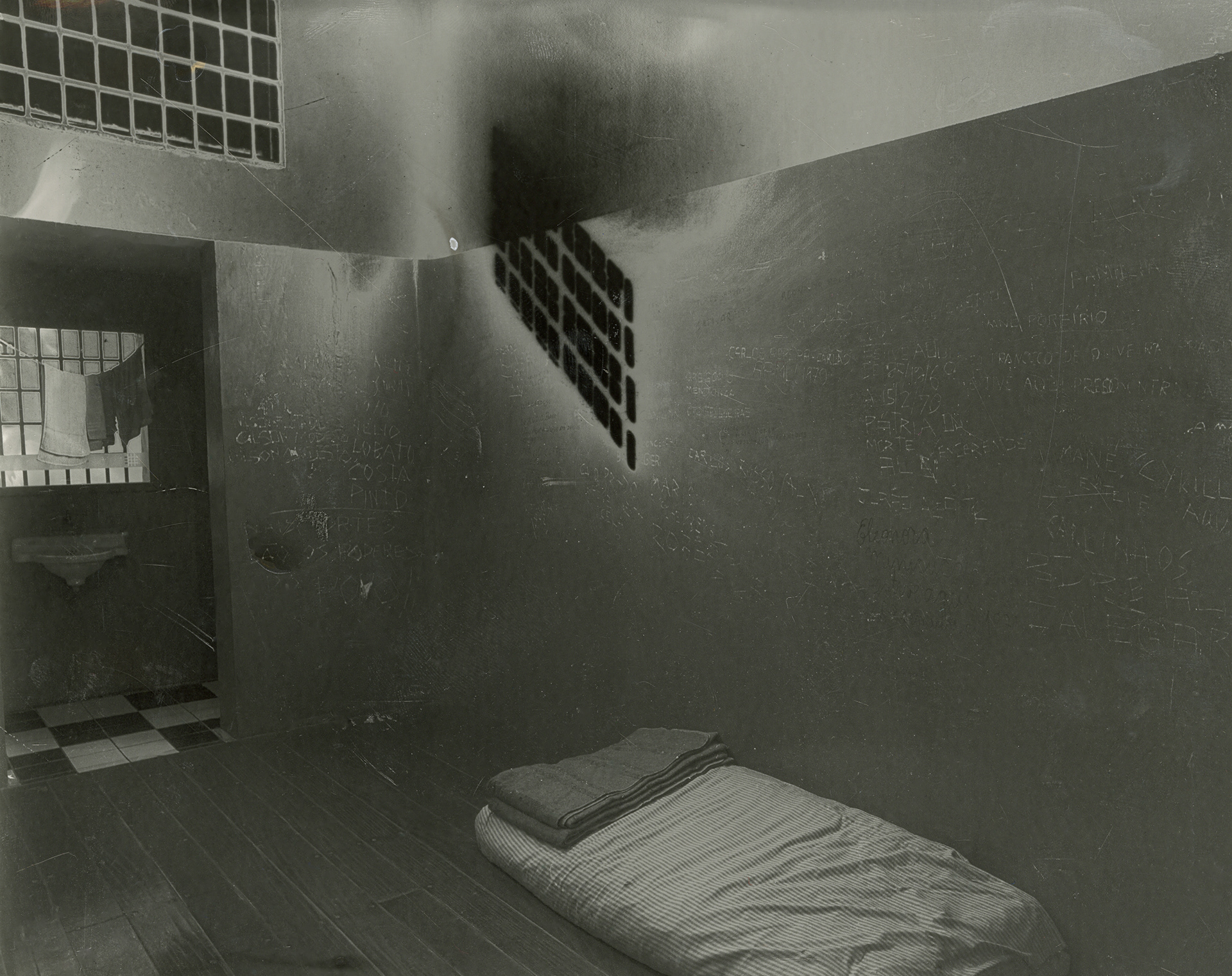

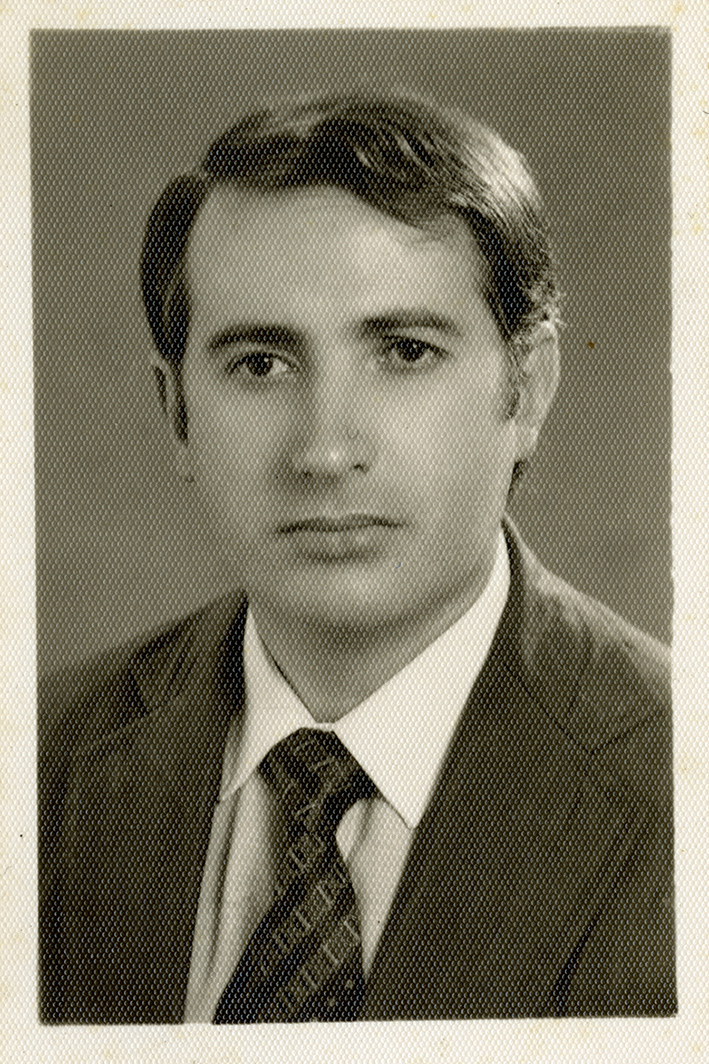

I still remember the excitement when my father came home after a long workday. I was five years old, a little girl with long brown hair who was stubborn and grumpy. I would wait anxiously for him and burst with happiness when he arrived, always with a gift, usually colouring pencils. I was his little princess. In the 90s, he retired after many years serving in the civil police of the state of São Paulo. I never really understood his job until I fell in love with history in high school. He worked in the Department of Social and Political Order, the DOPS; if you are Brazilian, you know what I am talking about. DOPS was the cruellest department in Brazilian history, created in the 50s during the Getúlio dictatorship and remained in operation throughout the civil-military dictatorship of 64. My father had a dual career during the civil-military dictatorship. He served as a police officer at DOPS and held a position at Bradesco Bank in the credit card department, where he accessed clients’ confidential information. The Brazilian government has failed to inquire into the activities of individuals like him, employed by Bradesco and DOPS. I delved deeply into my father’s career in the civil police. I unearthed an incident from 1979 when he was accused of extortion by Jose Osmar, a man who earned his livelihood by selling tickets for the municipal theatre. This story had been tucked away in the shadowy recesses of the Dops archive, and I employed solarisation to bring this chapter to light. Solarisation, pioneered by Sabatier in the 19th century, is a serendipitous process where the final results cannot be fully controlled. It involves waiting, developing, interrupting, and developing again. In some way, it speaks to the narrative of history – the need to pause to begin again, the uncertainty of waiting, and the ambiguity of the results to be achieved.

In 2020, Brazilian president Jair Messias Bolsonaro caused controversy during the COVID-19 pandemic when he remarked in an interview, “Those who are right-wing take chloroquine, those who are left-wing, Tubaína. This statement defended using a medicine that had not been proven effective against the COVID-19 virus. Tubaína is a popular soft drink in Brazil. To those not familiar with the details, the president’s comment may have seemed like a harmless suggestion for the left-wing individuals to enjoy a soda. However, researcher Marilia Moschkowich shed light on Twitter, pointing out that tubaína was a slang term used during the military dictatorship to refer to a type of torture that involved forced consumption of water until drowning. The fact that the former president referred to this torture method underscores the need for continued discussion about the country’s troubled past. Angela Davis aptly stated, “Freedom is a constant struggle”.